by Stephen Himes

Perhaps the most annoying type of film review is the “concern troll” review of a great film about a difficult subject.

During awards season, studios release civil rights/holocaust/slavery/women’s rights/gay rights/controversial politics/anti-war films that are well crafted, well received by audiences, and do a fair amount of business. The film may be a “message movie” from the “independent” arms of studios or financed by big stars as a prestige project (George Clooney, Brad Pitt, Ben Affleck, and Matt Damon are the current big benefactors of this style). Or, the film may be a more truly independent film bought by a big distributor (usually Harvey Weinstein) on the cheap, then promoted for awards to make a tidy profit from a smaller investment–2012’s “Beasts of the Southern Wild” about poverty in Louisiana, 2010’s “Winter’s Bone” about poverty in the Ozarks, and 2010’s “The Kids Are Alright” about a lesbian couple with children.

These movies are usually about outsiders, and they often promote a progressive agenda about poverty, equal rights, etc. Most film reviewers are more politically liberal than the average moviegoing audience, resulting in pushback–a polite way of saying “scathing, hate-filled emails and tweets” accusing them of being “a lefty apologist for communists” or “hating America” or “blaming everybody else for poor people’s problems.” And other such stuff that’s landed in my inbox over the years.

This is typical of many of my colleagues, which has amplified in the age of social media. As a result, professional film criticism has taken on an increasingly defensive tone: Critics, having been burned by overly forgiving reviews of films they’re politically sympathetic to, are hedging their bets.

Thus film criticism has largely become insiders writing about their own discomfort with writing about outsiders. Typically, these reviews ask, “I’m not questioning that this is a technically great film, but are we comfortable with the way this very sensitive material is approached?” The result is a passive, vague, and equivocating essay. Ultimately, the reviewer is more concerned about showing concern for the material than creating a clear evaluation of the film’s merits. In the end, the critic does a disservice to his own craft.

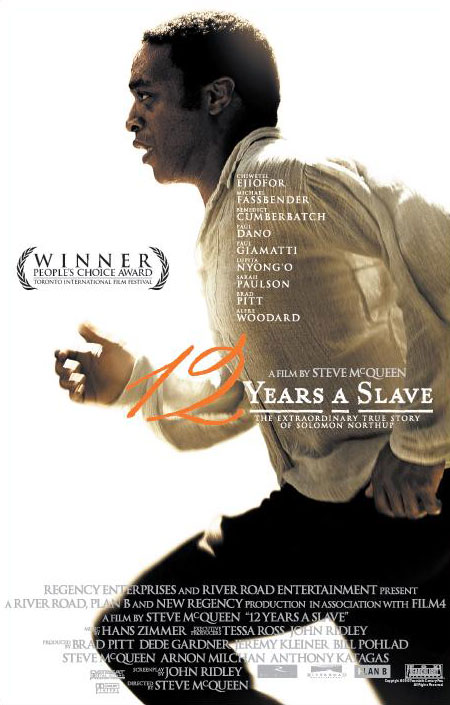

Mark Harris’ Grantland review of “12 Years a Slave” is one of those reviews. At Rotten Tomatoes, critics and audiences almost unanimously lauded the film (96% of critics, 94% of RT users). It’s the starkest depiction of slavery’s cruelty ever filmed. The film’s tone isn’t overly ham-handed, nor does it fall into the trap of using slavery as a metaphor for “America” or some big idea. It simply tells the story of Solomon Northrup, mostly as he wrote it in his memoir. Whatever “meaning” we attach to the story is entirely our own. Director Steve McQueen’s purpose is simply to confront us with the unvarnished truth about slavery. It’s a corrective to the “slavery wasn’t all that bad” argument that’s peddled by neo-Confederates and racists apologists even today.

By no means should “12 Years a Slave” be above criticism. But Harris’ review is wishy-washy kinda-criticism that obscures more than clarifies. He writes, “I remain somewhat ill at ease with a narrative strategy in which slavery is explored through a rarity within slavery”–the phrasing itself evokes a very considered kind of concern for…just…not…being…quite…sure…about…this. He’s concerned that the “12 Years” narrative is from the point of view of an educated, seemingly modern free man Northern Black, not a more common slave born into the institution in the South. Which leads to this astonishing statement, which deserves recounting in full:

“It’s a catch-22, because of course the singularity — the exceptionalism — of Northup’s narrative is one of the very things that makes it worth recounting, but any moment at which you’re invested in the particular injustice of his shackling is also a moment at which you may be insufficiently invested in the larger injustice of any slave’s shackling.”

In other words, Harris believes that when we watch the educated free man Northrup being whipped with a switch, with red splatters a flesh flecked across a prison cell, we’re only horrified because it’s happening to SOMEBODY LIKE US! Because, apparently, we can only empathize with people similar to ourselves, so we’re “insufficiently invested” in the suffering of the other slaves–as if we are unable to feel the horror of a female slave who is continually raped by her master, then whipped until her ribs show through her back. Harris doesn’t seem to think it’s possible for the audience to be wholly terrified by the entire situation, such as it’s told in the narrative. Or, as Harris further argues, that we can’t comprehend the cruelty of slavery because, you know, Northrup endured it for only twelve years!

The irony is that Harris seems to think the audience is too modern, detached, and self-absorbed to be sufficiently concerned about the cruelties depicted on the screen, but then he transitions into two paragraphs of movie awards talk–the very definition of modern detached self-absorption, especially for film critics, whose careers are mostly built around movie awards talk. The “challenge” for “12 Years a Slave,” as Harris sees it, is how awards voters answer the following question: “I liked it, but did I love it?”

Really, that’s what he thinks is running through viewers’ minds when they think back on “12 Years a Slave”? Not, “We should never underestimate the cruelty of slavery and its impact on the Black experience in America today,” or “Is it possible for a moral nation to be born out of such a dehumanizing practice?,” or “I am horrified by the possibility that I have that kind of cruelty in me,” or “The next time my racist uncle talks about how well slaves were treated, I am going to punch him in the mouth.” And that’s just what I, a white American male, was thinking.

Which leads Harris to the conclusion that Steve McQueen might just be too good at his job. Harris describes the infamous scene where Northup dangles from a rope for several minutes of screen time, subtly using the sun to convey the passage of hours. He barely scrapes his feet along the ground to keep from hanging, but in the background, “life goes on.” Harris writes:

“McQueen demands that you take in Solomon and what’s going on behind Solomon as part of a single fabric; he wants you to ask yourself if the other slaves are pretending indifference because they know that attending to Solomon could endanger them, or if they’re so numb to this level of cruelty and sadism that they can’t even see it.”

That’s a really good piece of criticism, which helped me understand what I was feeling during the scene: The horrifying thing is that they didn’t even see it. That’s the critic’s job, to use his/her expertise to give me insight into what I saw, to enrich my experience with the film. But then Harris again underestimates the audience’s capacity for empathy by arguing McQueen does too good a job conveying this point:

“The careful composition, the lighting, the showy bravura of his insistence on not cutting away all pull focus from the story and redirect it toward the storyteller.”

Only if you have little regard for the audience’s emotional intelligence. The scene is “overcalculated,” he says, as if the director should have been a little less careful in composing the scene–even though he just said the scene’s power comes directly from its composition in a single fabric. Any non film critic would see the scene and think, at a minimum, “Wow, slavery destroys the soul until people lose all capacity for basic human suffering.” As a critic, I will think back later about the composition of the scene and perhaps come to some different conclusion. But to say that effectively conveying a point directs the audience’s thoughts to the storyteller completely misunderstands how the vast majority of people see movies.

Though I’ve just spent most of this review criticizing him, I’ve usually found Mark Harris to be a sharp critic. But the passive, hedging, I-just-want-make-sure-we’re-not-all-missing-something-here nature of the review really rankled me. He turned his “concern” about “12 Years a Slave” into a passive-aggressive swipe at his audience by projecting his privileged insecurities onto us. Look, if you think Steve McQueen is a showy control freak who exploited Chiwetel Ejoifor’s soulful eyes into a film that actually devalues the cruelty of slavery, just say that. I can handle that, just as I can handle the unrelenting violence of “12 Years a Slave.” There’s no need to be “concerned” about how I’m going to see the film–it’s your job as the critic to help me see the movie through your eyes, like an actor does with a character. We’re all outsiders to a character who’s truly constructed as an individual–it’s the artist’s job to make us feel like we’re insiders.

There are few mistakes a white male reviewer can make that are more obnoxious than coming off like an outside voice of privilege, opining blindly on a world you can’t know. But this doesn’t mean that Wesley Morris, the African-American Pulitzer Prize winning critic, should have the only outstanding review at Grantland. Roger Ebert called movies an “empathy machine,” the artform that draws the viewer closest to another’s perspective. The outsider must imagine the other world, and can bring another useful perspective to the inside. Put forth your idea, martial your evidence, and explain your perspective. If you’re convincing, there’s no need to be “concerned” about what your reader will think.